What should we do with plastics?

By Mike Ritchie, MRA Consulting Group

Australia generates 2.4 million tonnes of plastic every year. It comes in all shapes and polymers. Car parts, sofas, drink containers, medical equipment, pallet wrap and single use packaging. You name a product in the economy and sure enough it will have plastic in it or in its supply chain.

Of the 2.4mt generated we recycle about 200kt and almost all of that is drink containers through either kerbside recycling or Container Deposit Schemes (CDS). There is a tiny amount of commercial plastic recovery in the form of pallet wrap, drink container recycling or silage wrap recovery. But by and large we landfill most plastic in the economy or well over 90%.

Sad but true.

So what should we be doing with plastic?

Well the first thing to do is to acknowledge its utility in most applications. It keeps food fresh for longer, it keeps medical equipment safe for use, it stops breakage of precious goods, it is lighter than steel so makes cars more efficient. The list goes on.

The second thing to say is that plastic is really only a pollution problem when it escapes to the environment as litter. Put another way, plastic is inert in landfill and will just sit there and break down into smaller pieces of plastic over decades. But it does little to no harm. It does not generate greenhouse gases in landfill (unlike organic waste) and it does not escape via leachate.

Often people conflate plastic in landfill with plastic in the environment and claim both as environmental disasters. They are not. Plastic in landfill is relatively harmless.

Plastic in landfill is a waste of (petroleum) resources but let’s keep it in perspective. We landfill about 2.4mt/yr but use 52,990ML of petroleum products. That is we lose about 4% of petroleum usage into landfill. If protecting resources is our key objective, we should switch all Australian transport and industry to solar/wind as a higher priority.

The key issue with plastic is environmental harm. We all know the statistics about the international growth in plastic pollution, the Great Pacific (Plastic) Garbage Patch, the sad images of sea birds etc. Littered plastic is a scourge in the environment.

Clearly the path we are on of permitting huge quantities of plastic to escape into the environment is not sustainable. But the key point here is that we should focus first and foremost on those plastic streams that more easily escape to the environment and those situations from which they escape.

Which leads us to some options.

Option 1. Ban all plastic. This would be massively counterproductive and is not even vaguely feasible. Banning plastic would result in more food waste, lower health standards, less reliable supply chains, a loss of lots of products that improve our standards of living. Bad idea.

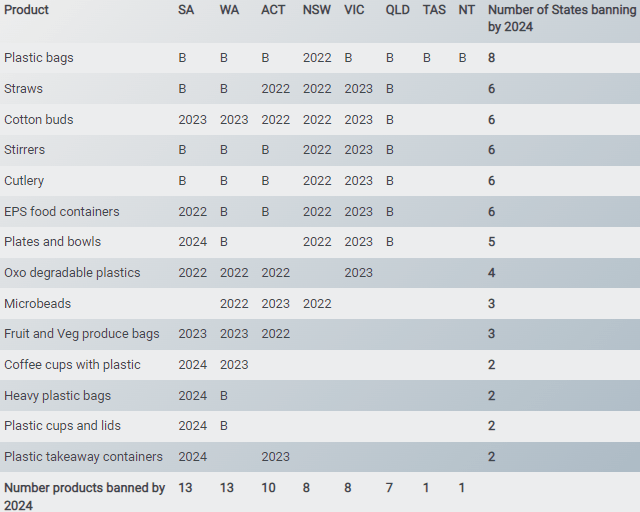

Option 2. Ban unnecessary plastic applications (or require substitution). That is, limit its use to where there are no reasonable substitutes AND its current use is causing harm. To their credit several State Governments with support of Federal and Local Governments have started down this path. Bans on polystyrene, single use plastic bags, straws and other single use items are on their way in many states. These are summarised in the table below (B=Banned; the Year is the announced ban date).

Sources: Corrs Chambers Westgarth; National Waste Action Plan 2019; AMCS 2020

But as you can see it is a very mixed bag. There is little consistency. The sooner all states get these bans done, the better.

While they are at it, I will add my list of uses of plastic that I think should be banned:

- Plastic stickers on fruit. They contaminate recycling. Make them out of something compostable.

- Plastic windows in envelopes. They can be paper and still see through.

- Plastic windows in bread bags. Ditto.

- Polystyrene pre-formed foam packaging e.g. the foam around your TV. It can be made out of formed cardboard.

- Polystyrene boxes for seafood and broccoli etc. There are good reusable substitutes.

- Plastic labels and sleeves on glass (and plastic) bottles. They form microplastics when glass sand is used in civil works (50% of all glass). They can easily be substituted.

Option 3. Collect and recycle it. (Most plastic in the environment arises from countries that have poor or non-existent recycling systems. (Not all but a lot). We should of course be supporting these countries to rapidly install household and commercial collection systems.)

In the Australian context we have good and efficient collection systems but we only recycle 10% of plastic because the economics are still broken.

It costs a lot to separate, aggregate and transport plastic (compared to other recyclables). It isn’t worth very much unless it is clean single polymer PET, HDPE, EPS or PP. Mixed plastic is currently worth $0 or thereabouts. So, spending money to go out and collect it, to make $0 revenue, is pretty dumb economics. That is why few do it.

So we need to either:

- Tax landfills more heavily (to change the economic balance between landfill and recycling); or

- Subsidise collection and processing via landfill levies or EPR (including funding Material Recovery Facilities, CDS, commercial collections); or

- Ban it from landfill (the economics will take care of itself because it cannot be cheaply disposed); or

- All of the above.

Once we have collected it, there are plenty of existing and emerging technologies to process and value add it. These include:

- Washing and optical sorting processes to convert mixed plastic to high grade single polymer streams such as rPET and rHDPE.

- Turn lower grade mixed plastic into furniture/flooring or other uses.

- Converting it into fuel via pyrolysis or catalytic conversion (rapidly emerging technologies).

- Make bespoke products out of it, such as Dresden glasses (small tonnes).

Option 4. Leave it in the residual stream and use Energy from Waste (EfW) to extract its energy value. Most governments accept that if material is truly residual and has no economic higher purpose then extracting its energy value makes sense. So, for plastic, we should recycle all we can but if it is otherwise going to landfill, we should consider EfWas a better alternative. (There are 2 EfW plants being built in Perth right now.)

Which leaves us to consider what to do about plastic escaping our recycling/landfill/EfW net and entering the environment. There are 3 ways it does so:

- Litter.

- Illegal dumping.

- Mistakes.

In my view the EPAs should significantly increase the penalties for all 3 of the above.

We should also use some of the $1.2 billion raised annually from landfill levies to fund an army of organisations and people, to clean up existing plastic pollution.

The CDS is claimed to have reduced litter by 40%. (I am a bit sceptical of the auditing methodology behind that claim.) But it is clearly having a positive effect on litter reduction. So we should do more CDS by adding more products and increasing the rebate to 20 cents per container.

Clearly, we need all governments to communicate the impacts of plastic on the environment and establish better incentives to do the right thing.

Conclusions.

To reduce our plastic problem, we should:

- Accept plastic’s overall utility and benefits.

- Ban the dumb things we use plastic for.

- Alter the economics to improve collection and recycling.

- Use EfW (or landfill) for the plastic that is uneconomic to recycle.

- Increase the penalties for pollution.

Mike Ritchie, is the Managing Director at MRA Consulting Group.

Search for other blog topics: