A link between rubbish and disaster

As the data from Clean Up Australia rolls in, what emerges most clearly is that the issue of waste is now undeniably linked to disaster on a wider scale.

Hundreds of thousands of dedicated volunteers ventured out earlier this year to clean up areas of bushland, coast, and city streets as part of Clean Up Australia Day 2022.

While flooding and heavy rains impacted on events along the eastern seaboard, those sites which were deemed safe proceeded with gusto – with many volunteers finding that litter is still hugely present in our environment, and this year, there have been some notable changes.

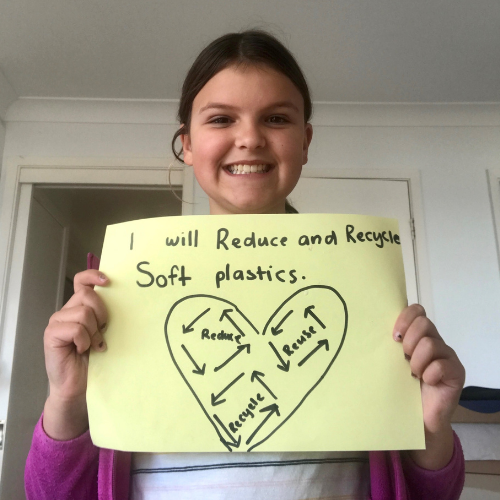

From polystyrene to soft plastics, aluminium cans and straws, takeaway coffee cups and food containers … Australia has it all. Clean Up Australia Day’s volunteer-submitted End of Clean Up Reports are testament to this.

But as the data rolls in, what emerges most clearly is that the issue of waste is now undeniably linked to disaster on a wider scale.

Many volunteers reported finding build-ups of debris on riverbanks and beaches, in the aftermath of flooding waters.

“High water level,” one volunteer wrote. Another specified an increase in rubbish due to “flood-made change”.

In some areas, volunteer efforts were redirected into immediate flood response, with the infamous 2011 Mud Army reforming in Brisbane, and troops of volunteers gathering in Lismore to pile sodden furniture, white goods, appliances, and bedding in metres-high mounds along the sludgy town streets.

It was reported that in Lismore during March, council, contractors and emergency personnel were collecting more than 1,000 tonnes of flood waste each day.

Meanwhile, the city mayor of Brisbane Adrian Schrinner said the 2022 floods had generated a year’s worth of landfill.

And flood waste is landfill – there is no question of recycling soaked-through materials, which breed mould and become unusable.

This year, many Clean Up sites also reported an increase in debris stemming from another current global disaster: the Covid-19 pandemic.

During the pandemic, online shopping and takeaway food deliveries increased dramatically, with residents resorting to ordering digitally while isolating as much as possible.

Keep-cups were put aside as cafes reverted to single use coffee cups, in an effort to contain the virus.

Not to mention the proliferation of at-home rapid antigen tests, the majority of which contain a 10-gram product, with 6 grams consisting of non-recyclable plastic.

Consequently, household waste increased, with Infrastructure Australia reporting a 20% increase nationally across 2020.

Face masks, latex gloves and sterilising wipes all featured on submitted End of Clean Up reports.

“We picked up masks for the first time,” one volunteer wrote.

Another volunteer indicated that the most significant change in their regular Clean Up site was the presence of wet wipes, “suspected to be used to sterilise and clean items due to Covid”.

The relatively new problem of single-use PPE materials has exploded on a global scale since the pandemic began.

A recent study on the repercussions of Covid-19 on the global plastic waste footprint estimated that globally, 3.4 billion facemasks are discarded daily.

That adds up to more than 100 billion discarded facemasks a month.

When we consider that plastics found in disposable masks can take up to 450 years to break down - the devastating link between world disasters and waste impact emerges.

It’s a confronting problem which in the Age of the Anthropocene – the current era characterised by man-made impact – requires enormous forethought.

Disasters throughout the world continue to increase.

And if those haunting images of piled-high rubbish in Lismore are anything to go by – as disasters increase, waste increases.

Clean Up Australia has taken on the task of collating data as to the quantity of facemasks discarded specifically onto Australian soils, by asking all participants to tally their mask findings.

While we’re still counting, anecdotally, an increase in Covid-related equipment in the environment is evident.

Everyday Clean Ups are of vital importance.

Now is also the time to plan for disaster and waste prevention and think about waste-management in the aftermath of disasters.

In what capacity could facemasks be recycled and reused to create furniture, infrastructure, or other useful items?

Researchers at RMIT University Melbourne have shown how disposable facemasks could be recycled to make roads, in an innovative circular economy solution to pandemic-generated waste.

The new material for roads would be made from a mix of shredded single-use masks and processed building rubble.

The new material would be capable of withstanding the pressures of heavy vehicles.

In that study, viruses on used facemasks were killed using a “microwave method”, in which masks were sprayed with an antiseptic solution then microwaved for one minute.

Professor Jie Lie from the RMIT School of Engineering research team said that by bringing circular economy thinking to Covid-generated waste issues, “we can develop the smart and sustainable solutions we need”.

With landfill currently overwhelmed by post-flood waste, it’s more important than ever to convert rubbish into resource.

Replas is one Australian company which since 1991 has been creating products such as outdoor furniture, bollards and decking from recycled plastic.

Since 2011, their partnership with REDCycle (who partners with Coles and Woolworths) has resulted in billions of pieces of soft plastic transformed into furniture, playground equipment and roads.

According to Replas, one of the current limitations of recycled plastic is that products made must be greater than 20mm thick, due to the mixing of a range of polymers.

It’s a limitation which might be overcome in the future through research and new technologies.

The recycled plastic sector holds the potential to expand toward much-needed residential products like indoor furnishings.

These are products which increase in demand in the aftermath of disaster.

The reality is, the greater society’s demand for recycled products, the faster new technologies can be achieved.

And new technologies might strengthen our cities, spare our environment, and prepare us for the unexpected.

Imagine a future where our waste – or our own masks – can be turned into useful items or infrastructure, rather than ending up in landfill.

That’s a future worth striving for.

Lucia Moon is Project Officer at Clean Up Australia

Search for other blog topics: